The University of Arizona is developing a global inundation model in collaboration with the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. The model uses VIIRS satellite imagery to map fractional inundation globally every day at 375-meters resolution. If deployed, the model will be NASA’s first operational flood mapping service which uses machine learning.

Continuity in flood monitoring after the end of MODIS data

After providing images of the Earth for more than 20 years through the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), in 2022 and 2023, NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites performed their final maneuvers and exited their constellations. With MODIS data provision set to end in 2025, remote sensing scientists are working to transition applications to the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) which has similar sensor characteristics to MODIS.

Among applications reliant on MODIS imagery is NASA’s Global Flood Product which has provided publicly-available surface water maps daily since 2012. With the ensuing end of MODIS data threatening to create a gap in NASA’s global inundation monitoring services, researchers in the University of Arizona’s Social [Pixel] Lab are working with collaborators at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center to develop a global algorithm using data from VIIRS, which will provide flood mapping applications well into the future.

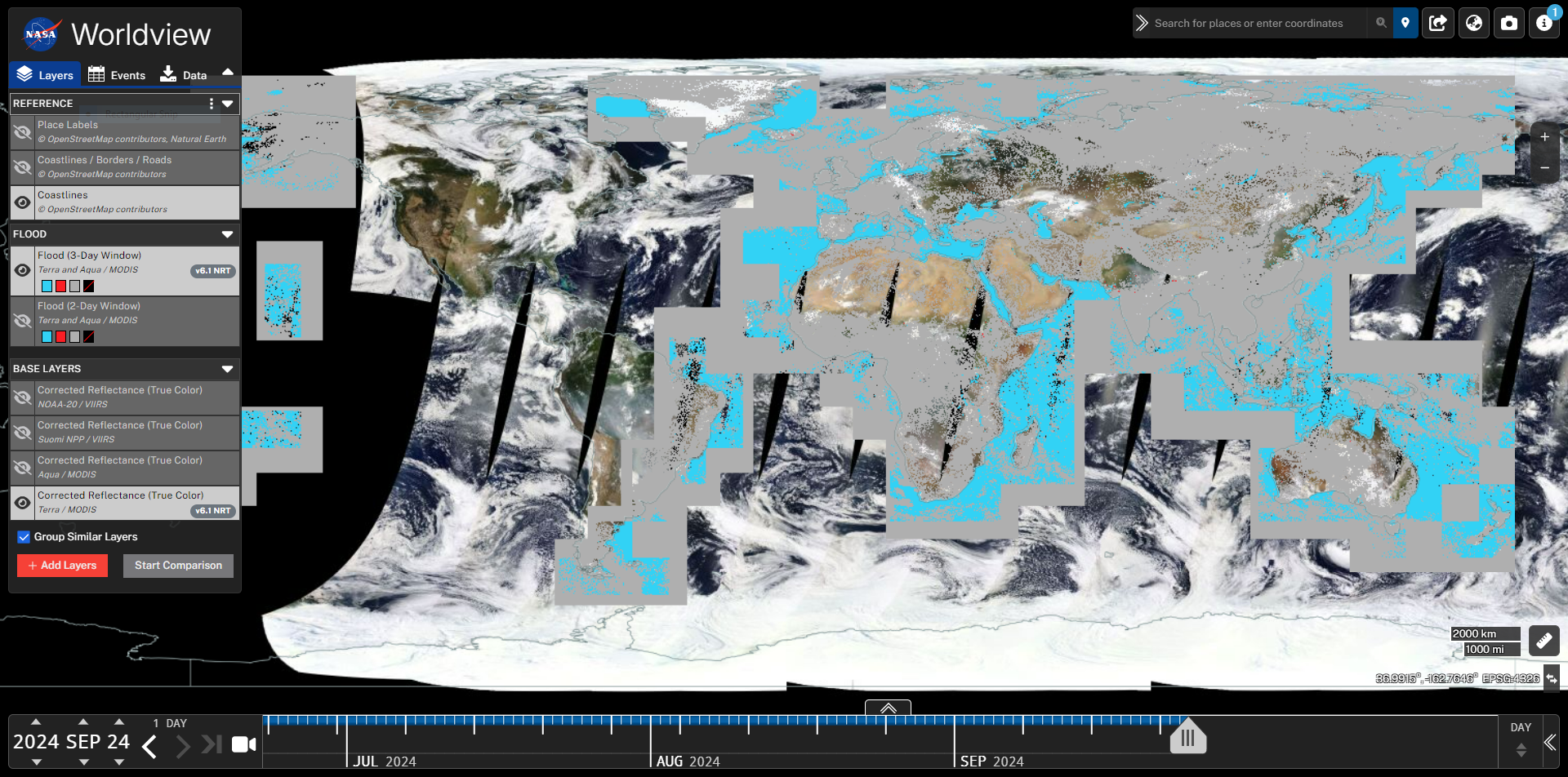

NASA’s current Near Real-Time Flood product uses daily MODIS data to detect flooded areas, and is available via NASA WorldView.

NASA’s current Near Real-Time Flood product uses daily MODIS data to detect flooded areas, and is available via NASA WorldView.

Transitioning to a deep learning approach

While NASA are working on a thresholding-based VIIRS inundation algorithm to provide continuity following the termination of MODIS data, this collaboration with the University of Arizona aims to enhance NASA’s inundation modeling capabilities making use of recent advances in machine learning. Our approach centers around convolutional neural networks, a form of deep learning model well suited to extracting helpful information from spatial imagery such as optical satellite data. While convolutional neural networks are not new to satellite inundation mapping, this project marks the first time that NASA has explored using machine learning in its public flood monitoring services, and the first time a global inundation model using VIIRS data has adopted a machine learning approach.

Training and testing a global model

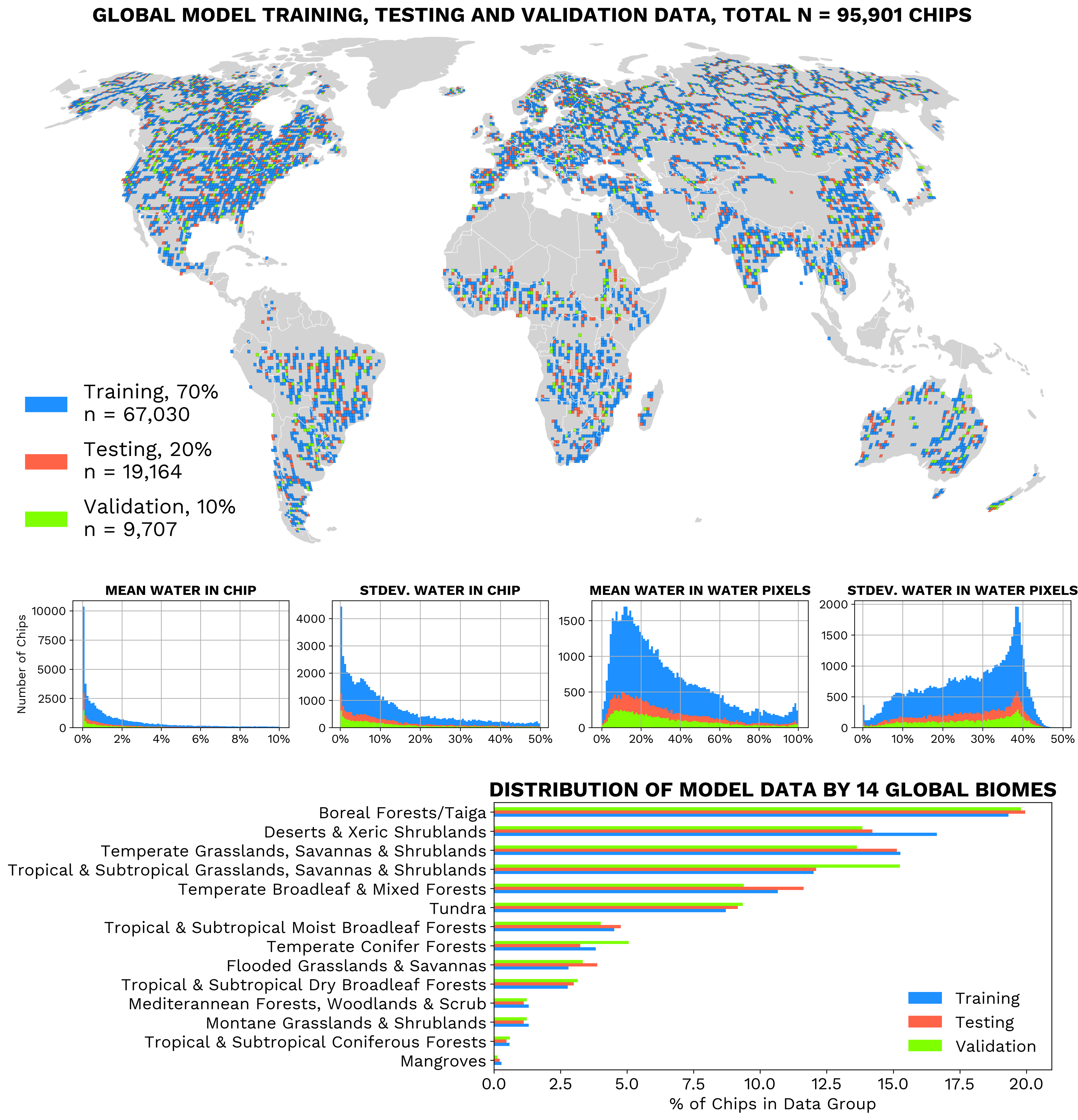

Developing a model that can reliably detect flood waters globally presents a major challenge given the diversity of land covers and types of flooding that can (and do) occur each year around the world. To train and test our model, we generated almost 100,000 individual water instances over the entire globe, each one consisting of more than 60,000 individual pixels and measuring nearly 100 by 100 km in size. While the dataset itself is important, we also paid careful attention to how we fed the data into the model, opting for a strategy of sampling by geography to encourage the model to transfer well to new flooding scenarios anywhere in the world.

To train and test our global model, we generated a comprehensive dataset of almost 100,000 water instances across diverse biomes and water characteristics.

To train and test our global model, we generated a comprehensive dataset of almost 100,000 water instances across diverse biomes and water characteristics.

In our second stage of global testing, we selected ten recent flood events across the world to quantify the model performance and compare with other global flood products. We are in the process of discussing the results with teams at NASA and look forward to sharing more details with the public later in 2025.

If you are interested, please take a look at the poster I presented at the American Geophysical Union’s Fall 2024 meeting which provides more information on key aspects of the project. You can also find this on my Presentations page along with many of my other public presentations.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Jonathan Giezendanner (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, previously University of Arizona) who initiated the project and developed the global deep learning framework including the model training data generation. Thanks also to PIs Beth Tellman (University of Arizona) and Fritz Policelli (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center).

This work is funded by grants from the NASA New Investigators (NIP) Program (80NSSC21K1044) and NASA Advanced Communications Capabilities for Exploration and Science Systems (ACCESS) Program (80NSSC23K1415).